Chicago’s built environment has garnered countless favorable descriptions in its nearly 200 year existence – Frank Lloyd Wright famously said “eventually, I think Chicago will be the most beautiful great city left in the world.” Though a high bar to clear, Chicago’s prominent architecture, breathtaking views of Lake Michigan and the Chicago River, and world-renowned parks have managed to mostly satisfy that narrative. Regrettably, one description related to Chicago’s built environment you would be hard pressed to find is equitable.

Between 1917 - 1920, nearly 1 million Black Americans migrated northward seeking political asylum from the deeply racist South. Despite a perception of greater participation in the democratic process, Northern cities like Chicago utilized other tools of suppression towards Black people in the mid-20th Century. One such tool, developed by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), was redlining, or a method in determining the credit worthiness of urban areas often driven by “racial compositions of neighborhoods.” The FHA often refused to back loans to Black people or others that lived near Black people. As Ta-Nehisi Coates succinctly puts it — “redlining destroyed the possibility of investment wherever Black people lived” (Coates).

This lack of investment in home ownership led to a stark disparity and disinvestment in other amenities such as food access, public transit, roadway maintenance, and access to parks and green space. In 2018, Chicago Non-Profit Friends of the Parks published a State of the Parks Report that described in great detail the disparity in access to green space between white, wealthy neighborhoods and Black, poor neighborhoods. Considering Chicago’s adopted motto is Urbs in Horto (City in a Garden), a motto that places emphasis on the importance of integrating natural beauty into an urban context, this 2018 Report is all the more alarming.

This brings us back to alleyways. Alleyways can be described as “narrow passages behind or between buildings,” meaning they are very much integrated into our built environment. This is especially true in Chicago, a city (mostly) based on a grid that holds the country’s most expansive alleyway network. Alleyways are often viewed as no frills and utilitarian given their nature of trash collection and service access. However, there are signs that even elements perceived as standard, like alleyways, are the result of and perpetuate inequities in Chicago. In this three part series, I intend on exploring the visionary Plan of Chicago, it’s contrasts with the racist policies of redlining and segregation, and how alleyways may serve as an alternative access solution.

Chicago’s Garden City Movement

In concurrence with its incorporation in 1837, colonizers established Urbs in Horto as Chicago’s official slogan. This was all despite “having few public parks,” as residents had only salvaged “two small parcels of the lakefront as parkland.” While the movement was still in its infancy stage and it was never explicitly stated, the idea of City in a Garden was clear; integrate parkland and green space throughout Chicago.

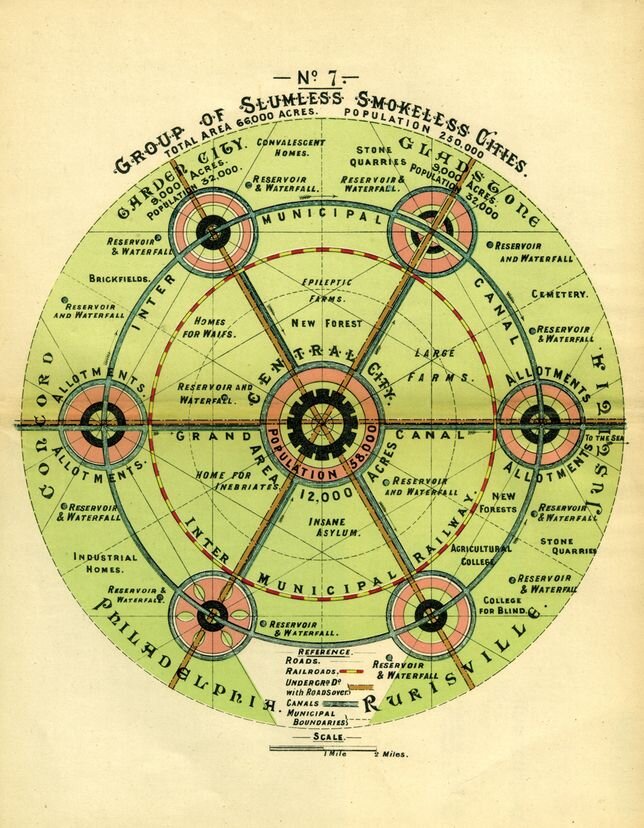

Later in the 19th century, Ebenezer Howard, a renowned urban planner, formally established the Garden City movement providing a possible blueprint for Chicago’s own Urbs in Horto. The Garden City movement was in response to the burgeoning industrial revolution, recognizing the need for an improvement in the quality of urban life. In Howard’s Garden City there existed five primary organizing features:

1. The purchase of a large area of agricultural land within a ring fence

2. The planning of a compact town surrounded by a wide rural belt

3. The accommodation of residents, industry, and agriculture within the town

4. The limitation of the extent of the town and prevention of encroachment upon the rural belt

5. The natural rise in land values to be used for the town’s own general welfare

Although Howard’s initial intention of how the City Garden looked – limiting residents to 30,000 people – interpretations of these organizing features recognized that recreational green space was a valid substitution as “agricultural” or “rural” land.

Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City concept. Courtesy of the British Cultural Studies.

In Howard’s 1898 book Tomorrow: a Peaceful Path to Real Reform we are first introduced to his drafted theoretical plan of The Garden City. In this theoretical concept, “the centre of the city would lay a garden ringed with the civic and cultural complex including the city hall, a concert hall, museum, theatre, library, and hospital.” Emanating from this core would be radial boulevards, punctuated by equidistant parks on the edge of the city. At its core, this plan is one based in equity by providing equivalent access to civic, commercial, and recreational amenities. Howard’s “Garden City movement is an early example of architects attempting to improve working-class people’s lives through redesigning the urban environment.” (University of Chicago).

Not long after this introduction to the Garden City, Daniel Burnham proposed his Plan of Chicago. Many of Howard’s initial concepts were baked into Burnham’s plan — providing a central core with radiating “parkway circuits” connecting a verdant “outer park system”. As seen in the image below, Burnham’s vision was ambitious, aiming to provide expansive views, ample access to green space, and an extraordinarily livable city.

An image from Burnham’s Plan of Chicago showing the ambitious radiating boulevards. Courtesy of the Chicago Architecture Center

Ambition, though, is often met with reality. Burnham’s grand vision of a Chicago was only partially realized, as over the next several decades a planning commission worked to “widen streets and boulevards” and provide “25 of the 29 miles of lakeshore to serve as public parkland.” Still, Burnham’s Plan of Chicago continues to serve as a reference point for the ongoing development of Chicago.

Redlining the Garden City

Daniel Burnham’s Plan for Chicago pre-dated one of the most important events to shape the modern-day Chicago: The Great Migration. After World War 1 “cut off immigration from Europe,” northern “labor recruiters headed into southern towns searching for a new labor supply” (Kendi, 308). Combined with the racist conditions of the Jim Crow South, Black people in the south elected to migrate en masse north to escape “menial jobs…barred voting” and perpetual racist violence. The Chicago Defender, an esteemed newspaper founded by and for Black people, played a significant role in influencing southern Black people to migrate north through job listings, editorials, and cartoons resulting in “110,000 coming to Chicago alone between 1916-1918” (WTTW).

The Chicago Defender's original building in Chicago, circa 1910s. Courtesy of the Chicago Tribune (Robert Sengstacke Abbott via Getty Images)

Between 1915 and 1940, Chicago’s Black population “more than doubled,” as an estimated “five hundred thousand African Americans ultimately moved to Chicago” (WTTW). This created a bustling and well-established community on Chicago’s South and West sides. Mirroring the Great Migration was an event of similar magnitude – the Great Depression. In 1933 emerged a stark housing shortage across the country. In response, the federal government developed a program to increase the housing stock. Their solution was the creation of the Federal Housing Administration; a seemingly ideal agency to address the housing shortage under FDR’s New Deal. This new agency would promote homeownership by backing loans, therefore guaranteeing mortgages.

Appallingly, these loans were only intended to assist white Americans towards homeownership – the U.S. was “opposed to the mixing of races” in the 1930’s (Satter, 41). To achieve this, the FHA developed maps which would help determine someone’s risk to default on a loan based on where they lived. This was, unsurprisingly, biased as White majority areas were deemed “Desirable” and denoted green on maps, while Black neighborhoods were deemed “Hazardous” and colored red on the maps. This made getting federally guaranteed mortgages nearly impossible for Black Americans in Chicago and other cities, leaving them to be exploited by “speculators” who would entrap them in housing contract schemes intended to scam buyers out of thousands of dollars (Satter). During the mid-20th century, it is estimated that “85 percent of all Black home buyers who bought in Chicago bought on contract”, an alarming figure that illustrates how difficult establishing sustainable wealth was for Black families in Chicago.

A “Redlined” map of Chicago. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Magazine

Fear and anger grew amongst white people who lived in redlined majority-Black communities and white-majority communities concerned that the addition of Black families would lessen their housing opportunities. According to the FHA the “presence of a single Black family was reason enough to refuse” a mortgage or loan to “an entire block” (Satter, 41). This was enough incentive for white families to resist and inflict violence against Black families looking to settle into white neighborhoods. This also led to many white families fleeing Black neighborhoods, draining significant amounts of resources out of these communities.

It took until 1968 for the federal government to partially address the wrongs done by the FHA and redlining. That year, the relatively new Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) crafted new legislation intended to “promote home ownership not just for white Americans, but also Black Americans and other minorities long excluded from FHA support” (Satter, 332). Although this landmark legislation is vital in ensuring fair housing practices and the equitable allocation of resources to communities, the momentum and devastation of redlining had already done significant damage.

Chicago Style Doublethink

In many ways the history of Chicago’s built environment is a perfect contradiction; a place where feats of architectural mastery conjoin with feats of developmental cruelty. The innovative and forward thinking Plan of Chicago has left an indelible imprint on how Chicagoans live. This imprint has not positively affected every Chicagoan in equal parts, much due to intentionally malicious acts against Black Chicagoans. Our modern Chicago remains deeply segregated and in need of equitable housing, planning, and design processes. The ideal of Urbs in Horto is egalitarian in principle, but remains far from being realized. An acknowledgement of past transgressions is a necessary step. With that said, there is still residual harm being done by past racist policies, as well as troubling patterns emerging from various corners of Chicago.

In part two of An Equitable Urbs in Horto we will analyze the current state of Chicago’s park system and infrastructure, and initiatives aimed at addressing the vast inequities found in both.

Works Cited

“1909 Plan of Chicago.” Architecture & Design Dictionary | Chicago Architecture Center, Chicago Architecture Center, www.architecture.org/learn/resources/architecture-dictionary/entry/1909-plan-of-chicago/.

Chopra, Swati. “Garden City.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2012, www.britannica.com/topic/garden-city-urban-planning.

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. “The Case for Reparations.” The Atlantic, June 2014, www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/.

“Early Chicago: The Great Migration.” WTTW Chicago, 11 Sept. 2018, interactive.wttw.com/dusable-to-obama/the-great-migration#:~:text=Five%20hundred%20thousand%20African%20Americans,to%20keep%20Chicago's%20factories%20rolling.

Irizarry, Juanita, et al. Friends of the Parks, 2018, State of the Parks 2018, www.fotp.org/uploads/1/3/3/6/133647985/state-of-the-parks-2018.pdf.

Jhori. A Dictionary of Modern Architecture, 16 Nov. 2015, voices.uchicago.edu/201504arth15709-01a2/2015/11/16/urban-planning/.

KENDI, DR IBRAM. STAMPED FROM THE BEGINNING. THE BODLEY HEAD LTD, 2017.

Satter, Beryl. Family Properties: How the Struggle over Race and Real Estate Transformed Chicago and Urban America. Henry Holt & Co., 2010.

Sniderman Bachrach, Julia. Park Districts, 2005, www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/955.html.